It’s been about a week, and I’m 30 hours into Fire Emblem: Fates Birthright. While that’s not the entirety of the game, it’s enough that I feel ready to start a preliminary discussion on its friendship mechanics, particularly with regards to how it compares to Bioware’s attempts to do something similar. More of that sort of musing after the break. (And if you’re familiar with the Fire Emblem series, you can probably skip to the final section.)

SRPG Starter Guide

I’ll start with the caveats: Aside from getting about 2/3 of the way through the 2003 Game Boy Advance Fire Emblem, Birthright is my first FE game, so I don’t have a lot to compare it to. And I haven’t played it enough yet to get any of the top-rank relationships, so there’s been no marriages or such yet. For that matter, it’s been about a year since my last Bioware game, so I may get some of the details wrong there too. Feel free to point out any inaccuracies in the comments. Be gentle.

For the unfamiliar, Birthright is a SJRPG–a strategy Japanese role-playing game. Essentially, they’re JRPGs that take the traditional menu-based approach to fighting, and put it on a grid, often featuring more simultaneously controllable characters than a typical JRPG. Due to some sort of quirk in game development history, this design is relatively rare in console-based gaming, but relatively common in computer-based gaming, to the point where a strategy RPG on computer means something more akin to the army-gathering/resource management of Heroes of Might and Magic.

A timeline of the SJRPG is beyond present scope; I’ll say my own experience is primarily from Shining Force, Final Fantasy Tactics, and Disgaea.

In terms of the options available in combat, SJRPGs are comparable to their “regular” menu-based brethren: during the player’s turn, they cycle through their party members, and can choose to attack, use an item, use a special ability, or just stand there; once the player is done making their choices, it’s the computer’s turn (or sometimes, playing order goes strictly in terms of some unit statistic, like agility) to do the same, and everyone alternates turns until one side is dead. There’s a lot of variation on that, but generally speaking, the biggest difference between the two types is that, as these screenshots suggest, in a SJRPG, the space the characters are in take a much more central role, and issues like positioning, range of attack, and movement distance become crucially important.

That’s SJRPG 101. For Fire Emblem: Fates, there’s a bunch of directions you can go in: the history of the series, the kerfuffle over translation issues, debates over the difficulty options offered in Fates, and the differences between Fates Birthright and Fates Conquest. But I want to focus now on Birthright‘s support system, and how it compares to the Bioware relationship system in terms of four factors: complexity, diversity, player-centrism, and game flow/ludonarrative dissonance.

Getting By with a Little Help From Your Friends

Let’s start with what the support system is. During a battle, the party member’s position in relation to the enemy character is obviously important; you have to stand close enough that your equipped weapon can reach it, and if that enemy character can reach the PM with its weapon too, it’s going to get a counterattack. There’s also a rock-paper-scissors system, where different weapon types are more effective against certain other weapon types.

But alongside the PM’s position in relation to enemy characters is the consideration of the PM’s position in relation to other party members. If two party members share the same space, they perform a pair up, where one is in front and the other is behind. In that mode, they move as one, where the member in front gets an attack bonus, the member in the back is shielded from attacks, and the front member is protected from Dual Strike attacks (more on that in a second).

There’s also an accumulation towards a Dual Guard, where (and there’s a random chance of it activating) the back member nullifies one attack on the front member. The downside to the pair up is that it halves the number of total attacks those two characters could have provided; I imagine I’d use it more, though, if I was playing on a higher difficulty where character permadeath was a thing, and thus defense play is more imperative.

If instead of occupying the same space, another party member is in an adjacent nondiagonal square, you perform a tag team attack. It boosts the attacker’s stats, and the supporter gets a hit in there too–what’s called a Dual Strike. The combined options of pair up and tag team attack is that they encourage the player to think in terms of the party as a whole, and keep characters bunched closely together. That could be disastrous in a game that has area of effect moves, but (so far, at least) Birthright has been relatively merciful on that front.

So far so good. If that was as far as the Fire Emblem series went, it’d be a nifty little system that adds some novelty to the combat. Where the system gets interesting, however, is that these supports grow stronger over time. Each time you pair two characters together and they support each other in a tag team or pair up (or a few other actions, including some non-battle actions, including a face-rubbing one that was pared down in the Western releases, but the tag team or pair up are the most common) the game keeps track, and once a certain number of support moments are reached, the bond levels up, from the basic case of C to A, A+, or S, depending on the pair.

The number of support moments needed varies from pairing to pairing, but it seems to grow higher for higher bond levels, and vary based on characters’ prior relationships and natural compatibility. (For example, sibling characters seem to develop bonds faster than many pairings, and some characters just can’t bond at all.) Once you’ve reached a new bond level, you go to the support menu outside of combat, and you have the option to view a brief dialogue scene between the two characters, where they discuss something that furthers their friendship, and advances some sort of minor subplot between them. For example, Hana and Subaki have various contests to determine who’s the better fighter; Hyato makes Mozu a charm to help her feel more confident in battle.

After you view the conversation, the bond level increases, and the characters enjoy a better stat boost in battle for future pairings. The conversations are generally simple and light, but they go a long way to establishing the series’ popularity among fans. SJRPGs also tend towards very large casts, which means that some characters never get any development beyond the initial scene they appear in, and FE shows a simple way that can be addressed.

The total number of pairings also gives the games a LOT of replay value, especially since each character can only have one A+ or S rank, and once it’s chosen, all others are blocked off. Finally, the support system adds another battle consideration, that players make decisions based on not what makes tactical sense, but what progresses the narratives they’re interested in.

Enough preamble! Have We Finally Gotten to the Bioware stuff?

Yes, we’re there. I find the relationship system in Birthright to be very interesting (obviously) and I thought the easiest way to reason out that interest would be to compare it to another RPG relationship system, that promoted in the Bioware game series, primarily Dragon Age and Mass Effect.(You could also make a rather interesting comparison with the Persona series, but that’s a different post.)

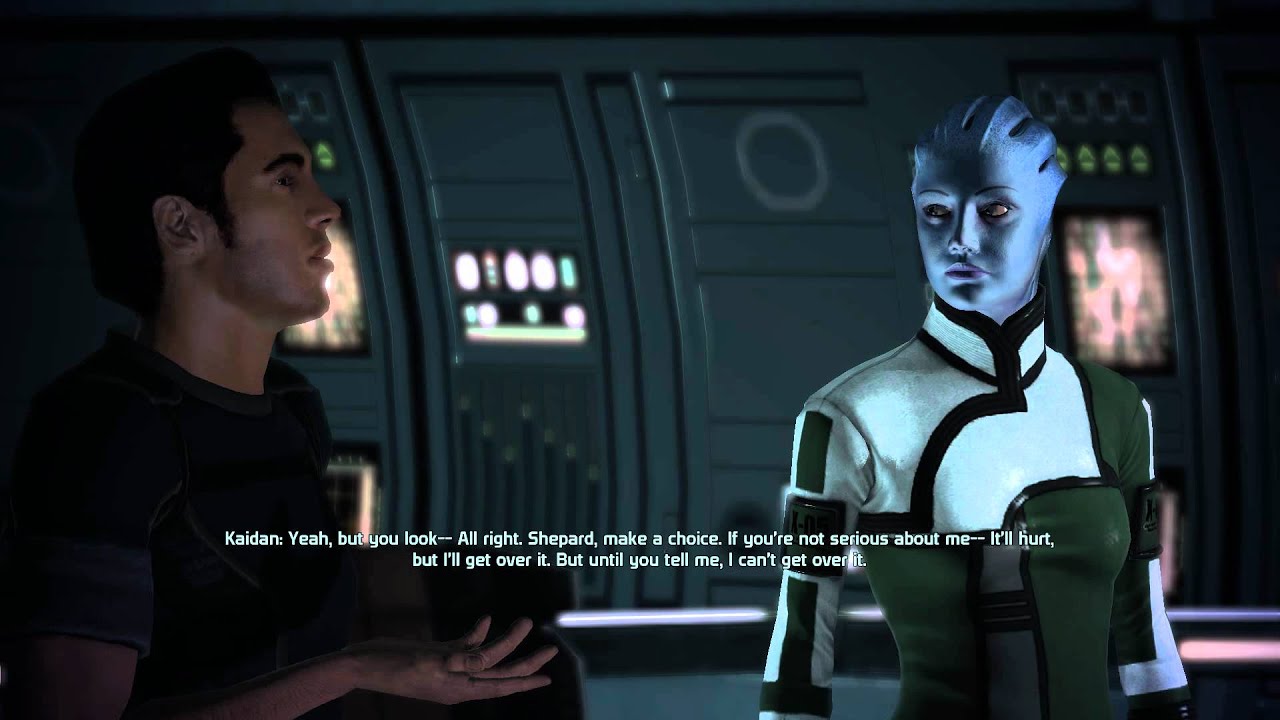

Without going into as much detail as with Fire Emblem (I recognize there’s a lot written Bioware relationships, and if anyone wants to swap links on that subject, I’d be really open to that in the comments), the Bioware relationship systems are largely (though not entirely) conversation-based, where the dialogue options you choose throughout the game influence how your party members feel about you. Players soon fall into a pattern: you go out and do some mission, then you return to your main base and see if the conversation options for your teammate have changed. It’s this fight and talk routine that came to mind when I played Fire Emblem. It’s the differences that interest me, though, and they are, again, complexity, diversity, player-centrism, and game flow/ludonarrative dissonance.

Complexity. Simply put, the engagement with the Bioware party member characters is more complex than in Birthright. I’m not saying the characters are inherently more complex–although I’d certainly lean that way–but there are many more options available. As entertaining as the Fire Emblem conversations can be, three or four pre-scripted scenes can’t really compare to dozens of hours of dialogue choices culminating in relationships that can have a much more nuanced arc. (And not necessarily a positive arc! I’m a big fan of Dragon Age 2‘s rivalry options.)

Diversity. This one’s worth keeping in mind, especially if, like me, you appreciate Bioware’s efforts towards queer representation. While there are often some questionable elements in their depiction of queer relationships, they’re probably at the forefront of mainstream videogames in that regard. In contrast, while Fates moves the series towards the possibility of gay relationships, it’s certainly not to the extent of the average Bioware game (although there’s room for improvement there too).

Player-centrism. The first two categories are, I’d say, in Bioware’s favor, but the second two are where Fire Emblem shines. When I’m looking for game narrative and play in RPGs, my preference is towards ensemble casts. To put it in comic book terms, I prefer series like X-Men that work on interpersonal drama as opposed to series like Superman where one character dominates. It’s why Final Fantasy VI is my favorite of the series, and why the multiple viewpoints of Suikoden III make it one of my favorite narratives in an RPG.

Western game development, for complicated historical reasons that are way outside the scope of this discussion, tends towards single character power fantasies. Bioware games buck this trend somewhat in that you are managing a party of characters, especially when switching between them in battle. But in terms of developing relationships, it’s their relationships to the player character that take center stage, above all others.

This centering creates weird situations where your PC is not just the strongest force in the game, but also the most sexually desirable or even just the most desirable in terms of friendship. The most striking representation of this the Dragon Age: Origins campfire, where a half dozen people are standing far away from each other by themselves, so the PC can engage with each one separately. Carried to extreme, this sort of framing shares a lot in common with the Japanese dating sim genre, and carries the same sort of uncomfortable quantification of relationships.

In contrast, I prefer the Fire Emblem situation, where you still have a lead character (and I think there’s more potential bonds with that character than any other) but the player can also witness friendships and relations that function independently of that centralizing force. Paradoxically, it makes the world feel more dispersed to me, that the lead isn’t the center of every encounter. There’s still that quantification of relationships (and if anything, the mechanics are laid more bare than in Bioware), but dispersing it among the team makes it feel more like playing with dolls than manipulating everyone to “kiss the ring” of the lead, so to speak.

Bioware’s not entirely devoid of character interaction that exists beyond the PC choice–relationships can develop apart from the PC, for example, though generally only if the player has decided not to romance either of them first. And the downside with the Fire Emblem pairing approach is that it doesn’t leave room for alternatives like, say, polyamory. But all in all, I prefer Fire Emblem’s ensemble approach.

Game flow/ludonarrative dissonance. Ludonarrative is the wrong word here, but it’ll get you thinking in the right direction. Generally speaking, I’m not one to care very much if game story and game action don’t match. Tolkien’s concept of secondary belief, as opposed to suspension of disbelief, is very much my starting point for engaging with any sort of fictional world. And yet, there’s something about RPGs in particular where there’s a mechanical dissonance–there’s a disconnect, frequently, between what you can do in an RPG town and what you can do in an RPG dungeon that creates a clear delineation between them.

In Bioware games, that often comes down to the difference between the fighting sections and the talking sections, the fight/talk pattern I mentioned earlier. I don’t have a problem with that alternation per se–games benefit greatly from down time between missions, in terms of both creating a good flow for play, and a good down beat in story.

My problem with Bioware games is that there traditionally hasn’t been very much interaction between the battle part and the story part. That is, the tactical choices you make when fighting some monster don’t often translate into conversational choices, or vice versa, with minor exceptions. In fact, the opposite holds true–because my PC was a rogue in Dragon Age: Inquisition, I was disincentivized from taking other rogues into battle with me for reasons of fighting redundancy, when they were the characters I was most interested in engaging with outside of battle.

I don’t mind if the game story doesn’t seem to fit onto the game’s action. But I do mind if the two types of action seem disjointed, especially if I greatly prefer one type of action over another.

Fire Emblem, on the other hand, creates a very direct link between the two halves through the Support system. The conversations come directly out of the bonds forged in battle, and the support you get from the bonds increases because you went through the conversation. I’m a fan of the flow that results–I want to go back into battle to unlock more conversations, and I want to do the conversations to get more fighting bonuses.

This close association also does a lot to keep the overall game linked; a Bioware game’s multiple quest lines are great, but it’s hard sometimes to stay focused on the overall goal. Fire Emblem is easier to focus on, for me at least, though part of that is admittedly just a big reduction in side-quests. But a welcome by-product here is that it makes the game’s narrative feel more cohesive, that you’re waging an ongoing, constant war. A Bioware game can lose that, especially through its open world approach.

I’m moving into speculation here, but I’d say that the significance of the bonds increases in the classic version of Fire Emblem. Birthright differs from some games in the series in that you can engage in optional battles to essentially grind your characters. In a lot of the games (and in Conquest, I think?) that’s not an option. You go from one story battle to the next, with brief story beats to catch your breath. Keep in mind the other limitations too: in FE classic, the number of bonds you can form is limited–once you set a certain number, you can’t do any more–and if a character dies, they’re gone forever, along with their support potential.

Those considerations dramatically change the player’s relationship to the support system. Now, you’re got an upper limit to how many turns of the game are going to happen, and thus a limit to how many supports you can realistically cultivate. Not everyone has time to become friends, and one wrong choice choice in a fight can preclude a friendship forever. A player has to decide what relationships matter to them, and what supports are worth pursuing. It’s a philosophy that goes directly counter to the “master every guild” approach of Skyrim or Oblivion. But I think there’s value there; this approach adds something very special to the bonds, that they’re these fragile things, difficult to forge in a world dominated by battle, but still worth striving towards, still meaningful to the characters that share them.

I’m not saying I always prefer playing that way–in fact, I quit Fire Emblem DS largely because I found its forward momentum too stressful–but it’s a very big difference from Bioware’s approach to combat, where anything short of a total party wipeout doesn’t really matter for long.

A lot of what I like about Bioware games and Fire Emblem probably don’t translate into each other. The complexity of a Bioware character doesn’t work easily when there’s a roster of thirty some characters and hundreds of pairing possibilities, for example, and Fire Emblem’s support relies on a turn-based system that Bioware has largely moved away from. But I think the comparison is worth making, to explore how different videogame processes create different models of what friendship and relationships can mean.